THE FRENCH DISPATCH

FRENCH CABLE STATION MUSEUM CELEBRATES 50 YEARS

By Kelly Cloonan

Text courtesy of and copyright © 2022 Cape Cod Life

Photography provided by French Cable Museum.

|

From the outside, the old French Cable Station in Orleans could be one of any old homes or buildings in the area. Driving past few might guess that inside, on a spring day in 1927, news arrived that Charles Lindbergh had safely completed a historical first–flying solo across the Atlantic Ocean.

“A young boy working here overheard,” recounts Joe Manas, the station-turned-museum’s president. “He ran to the local baseball field to tell everyone. He was so excited. He forgot to send the message to the rest of the U.S.” Manas chuckles as he tells the story. It’s one of many he shares during tours of the museum. Visitors come from all over the country and world to see the museum and hear about its history as both a station and now a historic landmark. This year marks the 50th anniversary the station has been a museum.

Joseph Manas, president of the |

The building served as a cable station from 1891 until 1959, receiving messages from Europe through telegram cables from France, spreading those messages to the rest of the U.S. During WWI, General Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, used the station to contact the U.S. government while he was working with European allies to defeat the Central Powers. The cable proved a mighty advantage to the Allies, so much so that in 1918, the Germans tried to damage the cable by sinking four barges off the coast of Orleans. They were unsuccessful, but the mere idea points to the cable station’s huge impact on wartime communication. Still today, cable is considered one of the safest ways to communicate sensitive information because it is impervious to hacking.

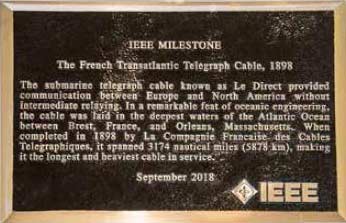

The new hot technology of communicating with cables first came to this country in 1844. The first, stretching from Baltimore to Washington D.C. in 1844, 40 miles long, was considered a huge feat of engineering. When the idea of a transatlantic cable was born, people were skeptical. At the time, a trip across the Atlantic took about two weeks by ship. Many ships encountered problems during their voyages, including heavy winds and storms. One out of six ships turned back, sank or were pushed off course. Engineers understood a transatlantic cable was crucial, but it was an enormous task to figure out how a cable could be stretched across more than 2,000 miles of ocean.

Award given to museum by Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers for direct Cable to Orleans from France. |

On land, cables were mounted on insulators and strung through the air. An undersea cable would need to be insulated too, since saltwater is a conductor. It would also need to lie on the uneven surface of the bottom of the ocean at two or three miles below sea level. Materials used needed to be both strong and flexible. Engineers developed a suitable cable using copper strands (for conductivity and flexibility), gutta percha (a material sourced from trees in Malaysia), jute yarn (to cushion the steel), and galvanized steel (for strength and protection from the elements). It took two ships to carry the 3,500 tons of cable. It took four attempts at laying the cable, the ships were finally successful when they met in the middle of the Atlantic, connected the cables, then parted ways, one heading east for Ireland and the other west for Newfoundland in 1858. Queen Victoria sent President Buchanan a congratulations message, and in just three hours, the president was able to respond—a huge improvement from the four-week wait time to which they were accustomed!

The original cable was too thin, which made the signal weak. A higher voltage burned ou the cable, so after six weeks of use, the cable was retired and two new ones were installed later in 1866, stretching from Ireland to Newfoundland. Then another cable on to New York. Due to the high cost of sending messages across the ocean, typically just the government and wealthy businesses could afford it.

Cable samples showing deep sea-cable, |

The French laid a cable to the U.S. in 1869, where it touched down in Duxbury, MA. Due to Duxbury’s busy shipping traffic, however, the cable was often damaged. In 1879, another cable was brought to North Eastham. In 1891 a new station was built in Orleans. The station closed in 1959 and is now a museum.

Owned by the French government, the station was not under American ownership until 1972, when ten residents of Orleans worked together to buy the building and turn it into a museum. Only two other similar museums exist—the Porthcurno Telegraph Museum in the U.K., and the Heart’s Content Cable Station in Newfoundland.

Stepping through the doors of the museum is a step back in time. In the superintendent’s office, an old typewriter and rotary phone perch atop an old oak desk overlooking Route 28’s busy traffic.

“The last superintendent to work here wasn’t a very big man,” Manas says with an amused grin, pointing to a chin-up pole across the door. “He did his exercises here.”

Manas says children are intrigued by the rotary phone, and often don’t know how to use it. The superintendent’s office also has an antique copy machine and a plaque naming the original founders of the museum, as well as a flag from St. Pierre, a French colony, where many of the operators came from. The station originally employed British operators since they were more experienced, but later they hired French operators who moved to Orleans and often stuck around long past the station’s close. “That’s why there are a lot of French names all over town,” Manas says.

A typewriter-like device that creates a paper tape with a message in Morse Code. Tape is then read and transmitted as telegram. |

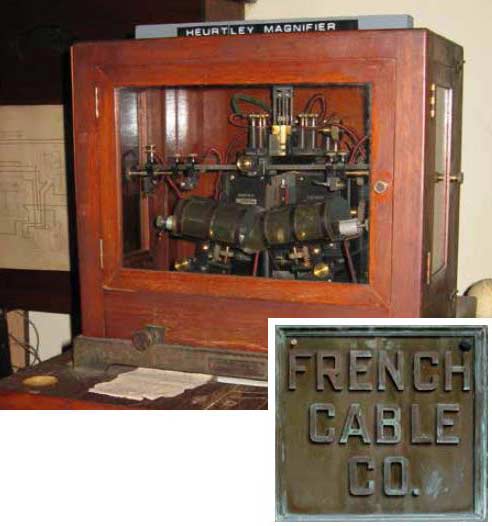

In the operations room, visitors learn how an operator read aloud messages coming in on the Marine Galvanometer; another operator recorded it and yet another operator transmitted the messages to New York or Washington D.C. Later, the Siphon Recorder was used to record the incoming signal, using a very thin glass tube to maximize efficiency. A mallet perforator allowed the operator to prepare the tape for transition, with individual strokes creating dots, dashes, and spaces for each letter. Later, the Kleinschmidt Perforator created the same tape, which could be read into the automatic transmitter, increasing accuracy and speed.

Small cards with Morse Code sit beside the perforator and visitors are encouraged to spell their names on the typewriter and take the thin paper tape as a souvenir.

Heurtley Magnifier increased signal with |

In the repair room, visitors can find the tools and equipment used to fix the cable, both close to shore as well as far out at sea. Manas points to the quiz board in this room, another interactive, hands-on activity for children, who can test their new knowledge by connecting a question to its answer with electrical cords. A correct answer results in a lit-up light bulb.

Beautiful old wood floors creak beneath the feet of visitors as they walk the hallway, where walls are covered with old photos and formal documents, some of which came from the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., and notes from visitors, many from children, who often send drawings and messages of thanks after visiting. The hallway also has a display dedicated to Cyrus Field, an American millionaire who helped fund the original transatlantic cable using the resources of his wealthy American and British friends. A smart businessman, Field sold pieces of the cable as souvenirs after the initial installation failure.

Copy of congressional medal given to Cyrus Field for first Atlantic Cable on display with artifacts. |

The tour is free, but donations are accepted. Volunteers, like Joe Manas, run the tours on weekends throughout the summer and love hearing visitors’ questions. Manas says that many visitors and volunteers have a personal connection to the station. “I would say about half our volunteers had some connection to a relative that had actually worked at the station,” he estimates. This personal connection gives a particular depth of emotion to the tour. Manas himself has a background in engineering, so he loves trying to fix the equipment when it stops working, often learning as he goes. After 12 years as president and even longer on the board, Manas says his favorite part about the museum is the people he’s met — both the volunteers and the visitors. “The people that come through are just so interested and get excited when I talk about different things,” he says. “Sometimes they know more than I do.”

The museum will continue to operate on a seasonal basis, with tours running every weekend from June through September.

Manas is excited to continue improving the museum with grants from the town of Orleans. The first was used to clean up much of the museum and equipment. Air conditioning was also installed to help with temperature control and preservation (and also the temperatures this summer). A new grant has been used to create a library room with environmental control . It will be used to store historical documents and provide a research room for interested students and researchers.

The museum offers a critical window on the past, Manas says, adding, “Back in the day, the cables tied the whole world together. It was the internet of the day.”

Kelly Cloonan is an editorial intern at Cape Cod Life Publications